The ₱3.5 Million Paper Trail: How Public Funds Built Private Enterprises

- THE LEDE: A BREACH OF FISCAL STEWARDSHIP

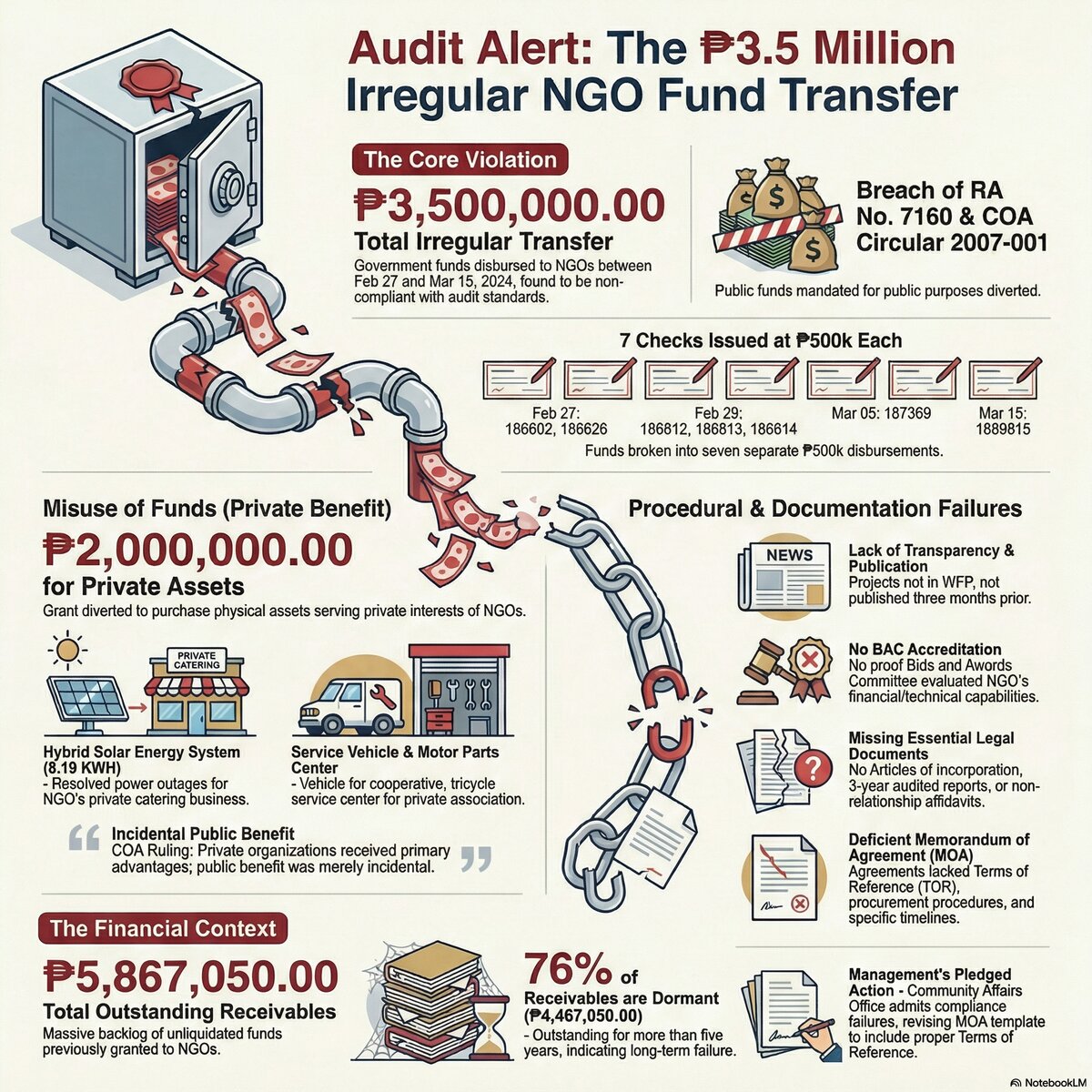

In the opening months of 2024, as the provincial administration moved to execute its annual budget, a series of financial maneuvers quietly diverted ₱3,500,000.00 into the accounts of select private organizations. What appeared on ledger lines as support for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) has since been exposed by state auditors as a fundamental deviation from the principles of public trust. This was not merely a administrative oversight; it represented a categorical breach of the safeguards designed to ensure that the public treasury serves a collective, rather than a narrow, private interest.

The core of the violation lies in a flagrant non-compliance with the Commission on Audit (COA) Circular No. 2007-001 and Section 305(b) of Republic Act No. 7160, which mandates that "Public funds must be for public purposes." These regulations serve as the bedrock of local fiscal administration, ensuring that taxpayer money is never used as a discretionary slush fund. By bypassing these statutory requirements, the province dismantled the primary defense mechanisms against the misappropriation of wealth, initiating a rapid-fire movement of cash between February 27 and March 15, 2024.

- THE ANATOMY OF THE DISBURSEMENTS

The movement of the ₱3.5 million was characterized by a rhythmic precision that suggests a calculated attempt to evade higher-tier oversight. Rather than a single, comprehensive grant subject to the rigors of a full project audit, the funds were liquidated through a "Seven Check" pattern. Each check was issued for exactly ₱500,000.00—a figure that serves as a common threshold in Philippine procurement law, often distinguishing "Small Value Procurement" from the more demanding requirements of "Public Bidding." By fragmenting the total into these identical, sub-threshold installments, the administration effectively obscured the scale of the transfer from the multi-layered scrutiny typically reserved for seven-figure disbursements.

Table 1: Chronology of Irregular Disbursements

Date Check Number Amount (PHP) February 27, 2024 186602 ₱500,000.00 February 27, 2024 186626 ₱500,000.00 February 29, 2024 186812 ₱500,000.00 February 29, 2024 186813 ₱500,000.00 February 29, 2024 186814 ₱500,000.00 March 05, 2024 187369 ₱500,000.00 March 15, 2024 1888815* ₱500,000.00 Total ₱3,500,000.00 *Note: The anomalous seven-digit check number on March 15 deviates from the established six-digit sequence, a discrepancy that warrants further investigative attention.

This methodical extraction of cash provided the liquid capital for a series of acquisitions that transformed the provincial treasury into a de facto venture capital fund for private entities.

- PRIVATE BENEFIT UNDER THE GUISE OF PUBLIC GOOD

A central tenet of public finance is that any benefit to a private entity must be strictly "incidental" to a primary public objective. However, the COA ruling on these 2024 grants found the inverse to be true: the primary advantage was pocketed by private organizations, while the public benefit was negligible or non-existent. Of the total grant, ₱2,000,000.00 was used to gift permanent capital assets to private groups, a blatant violation of the "public purpose" mandate.

The deconstruction of these acquisitions reveals a pattern of subsidizing private commerce:

- Solar Energy System: An 8.19 KWH Hybrid system was purchased to resolve power outages specifically for an NGO’s private catering business. This effectively used public money to underwrite the commercial overhead of a private competitor.

- Construction Materials: These were allocated to build a "child- and youth-friendly training space" situated within an NGO’s private premises, creating a permanent, fixed asset for a private group rather than a shared community facility.

- Tricycle Service Center: Public funds established a motor parts and service center for a specific association, essentially launching a private enterprise with state-provided startup capital.

- Service Vehicle: A vehicle was purchased for a cooperative, ostensibly to reach remote areas, yet it remains under the cooperative's direct control as a private asset rather than a provincial resource.

These are not public services; they are private subsidies. This transfer of wealth was facilitated by a near-total collapse of the province's internal "architecture of oversight."

- THE ARCHITECTURE OF OVERSIGHT FAILURE

Financial irregularities of this scale require a vacuum of accountability to thrive. The ₱3.5 million transfer was made possible by a systematic dismantling of the Bids and Awards Committee (BAC) accreditation process. The audit revealed a series of critical lapses that, when viewed together, suggest a deliberate bypass of transparency.

- Lack of Transparency and Publication: The projects were omitted from the Work and Financial Plan (WFP) and never published in newspapers or on bulletin boards as required by law. By failing to post these opportunities three months in advance, the administration effectively shuttered the windows of the treasury, preventing qualified organizations from competing for funds and keeping the public entirely in the dark.

- Zero Accreditation: There was no evidence that the BAC ever accredited these NGOs or evaluated their financial and technical capabilities. Without this vetting, there is no guarantee that these organizations possess the expertise or solvency to handle millions in public funds, leaving the province vulnerable to total loss.

- Absence of Legal Documentation: Basic requirements—Articles of Incorporation, three years of audited financial reports, and sworn affidavits of non-relationship—were missing. The province essentially handed money to entities whose legal identities and financial histories were unverified, inviting risks of fraud or nepotism.

- Deficiency in the Memorandum of Agreement (MOA): The MOAs lacked "Terms of Reference" (TOR), including procurement procedures and liquidation timelines. Without a legal roadmap, the province has no mechanism to demand the return of funds or prove how they were spent, rendering the contract virtually unenforceable.

These procedural failures are not isolated errors; they are a fresh layer on a sediment of long-term fiscal decay.

- THE ₱5.8 MILLION LEGACY: A PATTERN OF NEGLECT

The 2024 irregular transfers are a symptom of a chronic lack of accountability rather than an isolated incident. The ₱3.5 million is merely the latest addition to a mounting pile of unliquidated funds. Currently, the province holds ₱5,867,050.00 in outstanding receivables from NGOs—money that has left the treasury but has never been properly accounted for.

Even more damning is the fact that ₱4,467,050.00 of these funds have been classified as "dormant," remaining outstanding for more than five years. This indicates a systemic failure in monitoring and a profound lack of will to enforce the law. The 2024 irregularities are the predictable outcome of a culture that allows public money to remain in private hands indefinitely without consequence. This backlog of dormant funds drains the province's current fiscal health, as millions that could have been reinvested into legitimate public services remain trapped in unverified private accounts.

- THE OFFICIAL RESPONSE AND THE PATH TO RECTIFICATION

In the face of these audit findings, the provincial management’s defense has been characterized by a tepid, bureaucratic passivity. The Community Affairs Office acknowledged the lapse, admitting that several NGOs were simply "unable to comply with the requirements." Their proposed remedy—a promise to coordinate with the Planning Office and "revise MOA templates"—is little more than a bureaucratic bandage on a hemorrhaging treasury.

While updating documentation templates is a necessary administrative step, it does nothing to recover the ₱3.5 million already diverted into private assets or the ₱4.4 million in dormant funds. A "revised template" cannot replace the rigorous enforcement of existing law. To restore public trust, the province must move beyond clerical adjustments and commit to the strict adherence of COA guidelines. Only by enforcing the principle that public wealth must never be used for "incidental" public benefit while fueling private gain can the province begin to close the door on this legacy of fiscal mismanagement. ©️KuryenteNews