MANILA — A Manila trial court has ordered immigration authorities to bar Senator Jose “Jinggoy” P. Estrada and several former senior public works officials from leaving the Philippines, citing probable cause to believe they may attempt to evade prosecution in a sweeping corruption case tied to alleged anomalies in a national flood-control project.

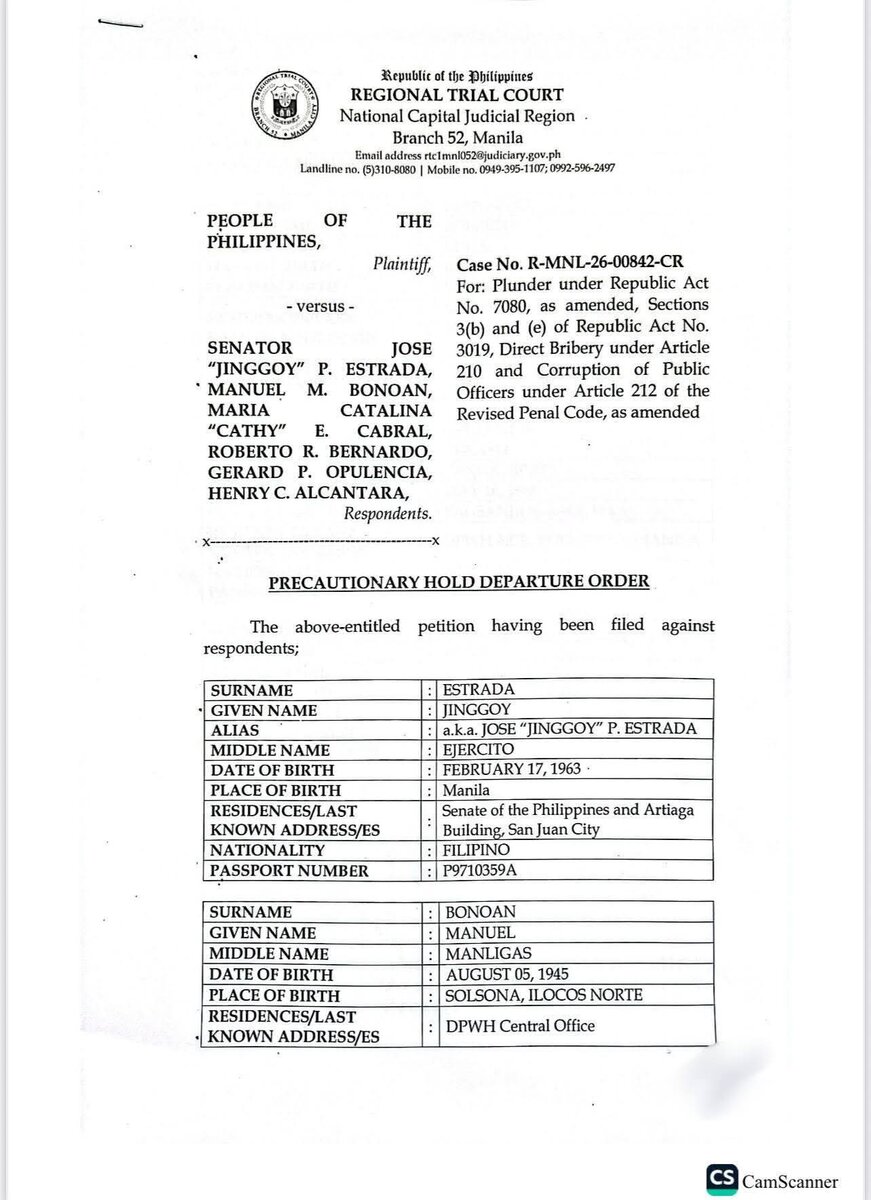

In a Precautionary Hold Departure Order dated Feb. 10, 2026, Judge Juan G. Rañola Jr. of Regional Trial Court Branch 52 in Manila directed the Bureau of Immigration to place Mr. Estrada and five co-respondents on the government’s hold-departure list while criminal proceedings advance.

The case, docketed as R-MNL-26-00842-CR, accuses the respondents of plunder, direct bribery and corruption of public officials — offenses that prosecutors say arose from irregularities in the planning and procurement of flood-control works. The charges invoke Republic Act No. 7080 (Plunder Law), Section 3(e) of Republic Act No. 3019 (Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act), and Articles 210 and 212 of the Revised Penal Code.

Named alongside Mr. Estrada in the order are Manuel M. Bonoan, a former secretary of the Department of Public Works and Highways; Roberto R. Bernardo, a former DPWH undersecretary; Gerard P. Opulencia; Henry C. Alcantara; and Maria Catalina “Cathy” E. Cabral.

The petition for the hold order was filed by the Department of Justice through its National Prosecution Service and the NBI-DOJ Public Works and Bid-Rigging Task Force. Assistant State Prosecutor Christine Fatima V. Estepa told the court that affidavits and supporting documents indicated a risk the respondents could depart the country to avoid arrest and prosecution.

“After examining under oath … supporting affidavits and documents, there is probable cause to believe that respondents will depart from the Philippines to evade arrest and prosecution,” Judge Rañola wrote in the order, which instructed the Bureau of Immigration to enforce the travel restriction immediately.

The Bureau of Immigration confirmed receipt of the order, according to Justice Department officials, and is required to include the respondents’ names in the government’s hold-departure database, which alerts border authorities at ports of exit nationwide.

The issuance of a hold-departure order does not determine guilt but is intended to preserve the court’s jurisdiction over accused persons in serious criminal cases. Under Philippine procedure, courts may issue such orders upon a finding of probable cause that an accused could flee or frustrate judicial proceedings.

The case traces back to a long-running investigation by the NBI-DOJ task force into alleged collusion and bribery in public-works contracting, particularly involving flood-mitigation projects. Prosecutors contend that the scheme involved manipulation of bidding processes and unlawful payments to public officials, potentially meeting the legal threshold for plunder — defined under Philippine law as the accumulation of ill-gotten wealth by a public official in combination with others through a series of overt criminal acts.

Mr. Estrada, a veteran politician and former Senate president pro tempore, has previously faced plunder charges in the so-called “pork barrel” scandal a decade ago, for which he was later granted executive clemency. The new allegations, however, relate to a separate infrastructure procurement investigation, according to court documents.

Mr. Bonoan, who served as public works secretary during part of the period under scrutiny, has also been a prominent figure in national infrastructure programs. Prosecutors have not publicly detailed the specific projects at issue, but court filings describe the case broadly as involving a “flood-control project anomaly” examined by the task force.

The order lists personal identifying information for each respondent, including birth dates and last known addresses, to ensure accurate enforcement by immigration authorities. It also directs that copies be furnished to the Bureau of Immigration commissioner and the Justice Department panel of prosecutors handling the case.

Legal analysts said the hold order signals that prosecutors have progressed beyond preliminary inquiry and are moving toward arrest or trial proceedings. “A hold-departure order is typically issued once a court has determined there is probable cause and jurisdiction over the accused,” said a Manila-based criminal law professor who requested anonymity to discuss the matter freely. “It ensures the accused remain within reach of the court.”

Under Philippine law, plunder is punishable by life imprisonment and forfeiture of ill-gotten assets. Conviction for graft or bribery offenses can also carry prison terms, perpetual disqualification from public office and asset confiscation.

Neither Mr. Estrada nor the other respondents have yet issued public statements on the hold order. Defense counsel could seek to lift or modify the restriction by filing motions before the issuing court, typically arguing absence of flight risk or posting of bail where allowed by law.

The court’s directive comes amid renewed scrutiny of public-works spending in disaster-mitigation programs, which account for billions of pesos annually in the national budget. Flood-control projects have historically been vulnerable to corruption risks because of their technical complexity and dispersed implementation across regions, according to watchdog groups and past audit reports.

Justice Department officials said the NBI-DOJ Public Works and Bid-Rigging Task Force has been pursuing multiple investigations into alleged procurement collusion across infrastructure sectors, including roads, bridges and flood-control works. The Estrada-linked case is among the most prominent to reach the courts.

The next procedural steps could include issuance of arrest warrants should the court find sufficient basis after evaluating the prosecution’s evidence, or the setting of arraignment dates if the accused are brought under the court’s jurisdiction. For now, the hold-departure order ensures that all six respondents remain in the Philippines while the case moves forward.

“SO ORDERED,” Judge Rañola wrote at the conclusion of the four-page directive, dated in Manila on Feb. 10 — a formal but consequential step in what prosecutors describe as a major corruption prosecution tied to public infrastructure spending.