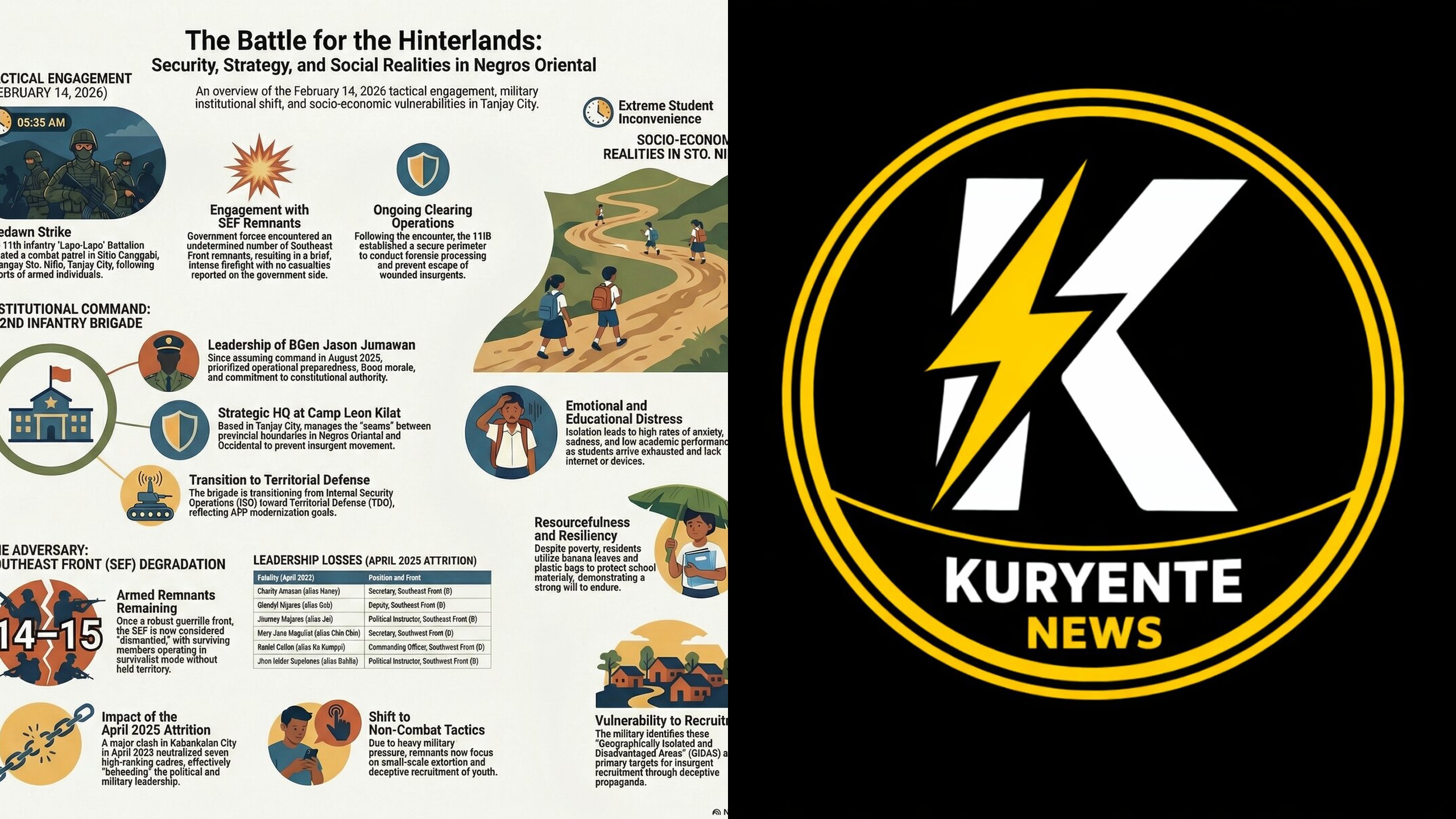

TANJAY CITY, Philippines— At 5:35 a.m. on Feb. 14, in the rugged hinterlands of Negros Oriental, a tactical engagement between Philippine Army troops and communist rebels broke the predawn silence of a remote village, signaling the enduring volatility of a decades-long insurgency the government has officially declared dismantled.

The firefight, which took place in the village of Sto. Niño, carried a sharp strategic irony: the insurgents were operating within the institutional shadow of Camp Leon Kilat, the very headquarters of the 302nd Infantry Brigade tasked with their eradication. Acting on local intelligence, the 11th Infantry Battalion engaged a fragmented cell of the Southeast Front, a unit of the New People’s Army that military officials previously insisted had been neutralized.

The clash represents a pivotal moment for the central Philippines, where the military is racing to transition from internal security to territorial defense. While the top leadership of the communist movement on Negros Island has been largely beheaded, the persistence of these mobile, fragmented cells underscores a "dismantled paradox": the ideological and geographic isolation of the island’s interior continues to provide sanctuary for a movement that is transitioning into a survivalist mode.

For the regional command, the stakes of these skirmishes extend far beyond the battlefield. The military is currently seeking "Stable Internal Peace and Security" status for the province, a designation that acts as a prerequisite for large-scale economic initiatives, including the Tamlang Valley Sustainable Agriculture project. Without this formal certification of peace, the "dismantled" label remains a military technicality rather than a civilian economic reality.

"The persistence of these armed remnants suggests that the insurgency is exploiting the very geographic and sociological distance the state has struggled to bridge," said one military official, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss ongoing operations.

The modern face of this rebellion is increasingly characterized by a shift from peasant recruitment to "urban-to-countryside" radicalization. This trend is epitomized by the case of Jhon Isidor Supelanas, a 26-year-old alumna of the University of the Philippines Cebu and a former student regent nominee. Ms. Supelanas, a transwoman activist, was killed in an April 2025 clash in Kabankalan while serving as a political instructor for the rebels.

The military’s data suggests a desperate state of attrition; Ms. Supelanas was found among the remnants of the Southeast Front, signaling a forced merger of depleted units. While student publications have framed her death as a response to state-sponsored violence, the criminal profiles of her companions suggested a darker alliance. Among those killed alongside Ms. Supelanas was Reniel Cellon, a commander with four outstanding warrants for murder, and Charity Amacan, a front secretary facing 11 murder charges.

Military commanders have used the death of Ms. Supelanas as a cautionary tale, characterizing the movement as a "futile cause" that consumes the region’s intellectual capital.

Yet, the terrain itself remains the rebels' most effective recruiter. In Sto. Niño, located at an elevation of 550 meters, the reality of "Geographically Isolated and Disadvantaged Areas" provides a vacuum of state presence. Students in the village often walk up to six kilometers daily through rugged terrain, sometimes using banana leaves as umbrellas and plastic bags to protect their textbooks.

A study by Joseph Torres, a researcher who has documented life in these "isolated" areas, suggests that the exhaustion and lack of infrastructure in the hinterlands create a psychological distance from the state. When children walk barefoot to classrooms that lack internet or cellular signals, the military’s "Whole-of-Nation" strategy recognizes that a new road or a functioning cell tower is as tactically significant as a rifle company.

The leadership of the 302nd Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General Jason Jumawan, has recently been tested by a dual-mission challenge. On Feb. 11, a magnitude 6.9 earthquake devastated northern Cebu, requiring the urgent deployment of engineering and civil-military units. Within 72 hours, the command managed a massive disaster response while simultaneously executing the Tanjay City strike.

Despite these operational successes, the military and police forces face internal pressures. In January, Police Sergeant Bonifacio Saycon allegedly killed four people, including a municipal police chief, in Sibulan. This was followed on Feb. 9 by a fatal shooting at Camp Gen. Macario Peralta in Capiz, where a soldier was killed by a comrade during a social gathering.

Lieutenant General Jose Melencio Nartatez, the acting chief of the Philippine National Police, has responded with a "zero tolerance" policy regarding psychological fitness. These internal failures, framed by the pressure of protracted internal operations, represent a domestic threat to public trust that commanders must manage alongside the insurgency.

As the Philippine Army evolves toward territorial defense, the battle is shifting from the forest to the airwaves. Through "Sugilanon sa Kabukiran," a radio drama aimed at the hinterlands, the military is attempting to offer a narrative exit for those still in the mountains.

The long-term stability of Negros Oriental, however, will likely not be determined by the exchange of fire at 5:35 a.m., but by whether the state can finally close the distance to places like Sto. Niño. Until the infrastructure of the government reaches the "bare feet" of the interior, the conflict remains an unfinished chapter.